As a child, Lytle Denny learned where blue grouse, ruffed grouse, sharp-tailed grouse and greater sage grouse lived. A member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, he scouted the high-desert landscape during family hunting trips on the tribes’ ancestral homelands in southeastern Idaho. His dad preferred hunting deer and elk, but Denny developed an affinity for grouse.

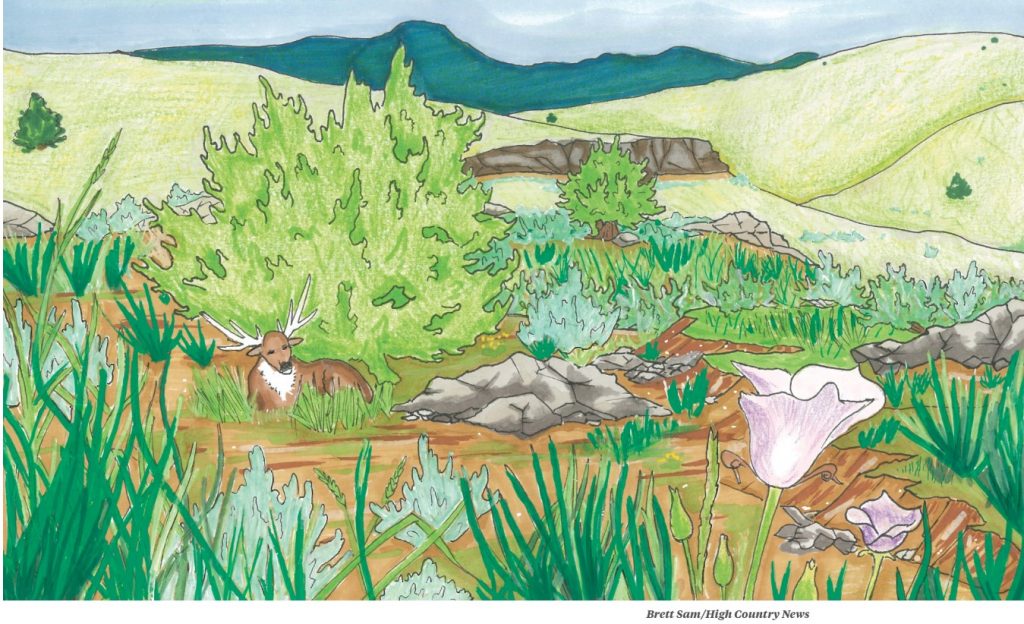

The family hunted together as a group. Denny moved quietly through the silver-green sagebrush, hoping to hear the sudden heavy wingbeats of a startled bird. His family watched, waiting for a flush, not just of grouse but of mammals, too. “So it worked together,” he said. “We’d get birds and big game.” READ MORE

Rare bird: Sage grouse are both unique and imperiled

Much of sage grouse physiology and behavior — from the yellow air sacs that males inflate during mating displays to the species’ preference for eating plants — is unusual for a bird.

Avian evolution has favored light weight for easier flight, leading to hollow bones and small organs. But sage grouse evolved “heavy machinery,” as Boise State University researcher Jennifer Forbey described it — large organs and specialized guts — to digest sagebrush leaves, which are toxic to most animals.

From September to February, sage grouse eat sagebrush almost exclusively, preferring the tiny, silver-green leaves of low-growing species like early and mountain big sage. Scientists have found that these species fluoresce under ultraviolet light due to chemical properties in their leaves. Sage grouse have photoreceptors in their eyes that allow them to see UV light, and researchers like Forbey think that this glow may help the birds locate the plants. Female grouse teach their chicks where to find food, passing on what Forbey called “nutritional wisdom.” Both males and females return to the same breeding, nesting and chick-rearing sites every year, generation after generation.

But the birds’ loyalty and diet are no longer well-suited for today’s landscape, transformed since settlers arrived.

Every year, 1.3 million acres of sagebrush steppe is lost, primarily to wildfires fueled by cheatgrass that has spread, in part, by way of extensive livestock grazing. Unfortunately, animals that rely heavily on one food source — like koalas, pandas and sage grouse — “tend to be the most vulnerable to extinction,” Forbey said. — Josephine Woolington