The U.S. Forest Service has been searching for an identity almost since the federal government began managing trees in the 19th century.

It started in 1876 inventorying public lands to prevent over-logging. Then it became the lumber provider to the nation. Now, just shy of its 150th birthday, the Forest Service faces another fundamental reorganization announced by Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins last week.

Or not. A week after Rollins’ announcement, the Senate Agriculture Committee ordered Deputy Agriculture Secretary Stephen Vaden to present a “Review of the USDA Reorganization Proposal.” Many public lands watchdogs hoped the Wednesday hearing would clarify where the idea came from and how the Forest Service’s tree focus fit in the farm-and-ranch world of the Department of Agriculture.

During the hearing on July 30, Committee Chairman John Boozman, R-Arkansas, offered his appreciation that Vaden, who took the job just two weeks before Rollins announced the reorganization on July 24, was working on his third week when he was summoned to explain the plan.

Ranking member Senator Amy Klobuchar, D-Minnesota, was less welcoming.

“The reason for the short notice is because the administration put out a half-baked plan with no notice,” Klobuchar said. Rearranging a major department that had already lost 15,000 staff members at a time when tariffs and pests such as the screwworm are roiling farm markets is “nothing short of a disaster,” she said.

Sharon Friedman, former Forest Service regional planning director, called the Rollins memo “way out of the normal range of ‘things to do.’” In particular, she pointed to the proposal to phase out Forest Service regional offices, instead of shrink them from the current nine to some smaller number. Earlier this year, draft maps showing a two- or three-region compression were in circulation.

“I think Congress is going to say this is a really stupid, bad idea,” Friedman told Mountain Journal on July 29 ahead of the hearing. “Go back to the drawing board.”

The National Association of Forest Service Retirees was equally aghast. “We do not see anything in the proposal that would improve services or efficiency,” they wrote in a July 29 letter to Senate committee leaders Boozeman and Klobuchar. “Rather, it appears to simply cut staffing and funding without describing how the work will continue to get done. It provides the classic direction to do more with less.”

NAFSR Chairman Steve Ellis told Mountain Journal the proposed reorganization of the Forest Service is nothing new. “I’ve been through a lot of these in my career, going back to when Jimmy Carter was in the White House,” he said. “The political ones are easy to smell, and this has the political smell to it. I doubt that it came from the Forest Service. It came from higher up. They were told ‘Eliminate regional offices and station offices — figure it out.’”

Where to call home?

While the impact that Rollins’ reorganization plan might have on the Forest Service has drawn particular attention, it affects all 29 agencies within the Agriculture Department. Rollins told Politico on Friday that “perhaps 50 to 70 percent of our Washington, D.C. staff will want to move” to five new hubs the agency is creating and the rest should seek jobs in the private sector.

That amounts to about 2,600 of the 4,600 USDA staff now in Washington, D.C. offices. The department has about 100,000 employees nationwide, 90 percent of whom work outside the national headquarters area.

The regional hubs would be in Raleigh, North Carolina; Kansas City, Missouri; Indianapolis, Indiana; Fort Collins, Colorado; and Salt Lake City, Utah. The memo did not say if the Forest Service regional offices would be redistributed among those five cities or eliminated altogether.

Vaden told senators that the plan removed some layers of middle management. “But that does not automatically mean everyone located in a former regional office of an agency will be moved,” he said. Vaden also pledged that USDA would help with moving costs for current employees, while “building the next generation of USDA leadership” in the regional hubs.

Most of Wednesday’s Senate hearing focused on two issues: Why there was so little advance notice of the plan and what senators’ districts were being considered for receiving the USDA jobs Rollins was moving out of Washington, D.C.

Senator John Hoeven, R-North Dakota, praised the reorganization’s goals, but warned he needed to see more collaboration with Congress.

“There’s a difference between you selecting hubs on your own and if we work together and come up with a plan,” Hoeven said. “Is this an outcome that we’re going to talk about, or a fait accompli?”

But Vaden did reveal a few expectations for the Forest Service.

Senator Ben Jay Luján, D-New Mexico, asked about the impact of “eliminating a regional office” of the Forest Service. Vaden replied that the Forest Service’s national human resources office in Albuquerque would not be affected in the reorganization, but that “the regional office will no longer be there.” Its building is already on a federal list to be closed and sold, and its employees would “be absorbed to other areas or asked to move.”

In his testimony, Vaden said one of the biggest reasons for the organization was to get the USDA workforce out of the National Capitol Region, which has “one of the highest costs of living in the country.” Federal salaries include a “locality rate,” or pay boost, to help employees afford expensive areas. The Washington, D.C. locality rate is 33.94 percent above a federal job’s base pay. Federal workers with new families couldn’t afford to buy homes in the Capitol area, where prices are averaging more than $800,000, he said.

What saves money?

“If you’re really looking for savings and belt tightening, focusing on the higher level of the organization doesn’t bother me,” said Mary Erickson, the recently retired supervisor of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. “It’s not like you couldn’t downsize the regional offices, but the transitional costs of that are daunting. As you eliminate regional offices, where does that work go? And how do you do that in a year’s time? That’s a lot of work. And they say they don’t want to do this in fire season. Those are pretty long these days.”

Erickson pointed out that Fort Collins’ locality rate is 30.52 percent, resulting in almost no payroll savings. And although Salt Lake City’s locality rate is 17.06 percent, Utah’s public land is predominantly managed by Interior’s Bureau of Land Management, not the Forest Service.

“There’s been no explanation for those locations,” Erickson said. “No one seems to know who’s the mastermind behind this design.”

Nor does there appear to be any acknowledgement of previous federal reorganization attempts. Congress created a Special Agent in the Agriculture Department to survey the nation’s public forests in 1876, and opened a Division of Forestry in 1881. A decade later, Congress passed oversight of “forest reserves” to the Interior Department. President Theodore Roosevelt moved it back to Agriculture in 1905, naming Gifford Pinchot the first chief of the Forest Service.

An official history of the Forest Service’s first century labels eight more evolutions, including “The War Years,” “Environmentalism/Public Participation Era” and “Ecosystem Management and the Future Era.”

Ellis recalled the attempt at slimming down the BLM during the Clinton administration.

“They decided to take the district office layer out, which is like removing the forest supervisor layer in the National Forest System,” Ellis said. “It ended up costing a lot of money to move people around and get out of office leases. It ended up being a total flop. When the second Bush administration came on, they quietly put that layer back in.”

The first Trump administration took a similar track in 2019 when it moved the BLM headquarters out of Washington, D.C. Staff were dispersed to new offices in Colorado, Nevada, Utah and several other bases.

A 2021 survey of BLM workers by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility reported that 87 percent of reassigned employees either retired or quit rather than move. The field offices were staffed largely by new hires who lacked the scientific or experiential backgrounds of the former staff. “This lack of expertise in new hires has resulted in a shunning of science at the agency, and even a demonization of intellectual culture in some cases,” the PEER report stated.

It also resulted in a paucity of workers handling public business. At the time, the Utah area reported an average of one BLM employee for every 37,277 acres of public land. Arches National Park, which is surrounded by BLM lands, had one employee for every 1,530 acres.

Biden administration Interior Secretary Tracy Stone-Manning moved much of the BLM headquarters staff back to Washington in 2022. But she also reinforced the Colorado office, expanding its contingent from 27 positions under Trump to 56.

Friedman now runs the forestry policy blog Smokey Wire. She was a planning director in 2007 when a “Transformation Team” explored ways of performing Forest Service duties better. It did not appear to consider moving to another part of the federal org chart, such as Interior. But Friedman noted her own inability to find out what it actually accomplished: “I couldn’t find any documentation for the effort. It wasn’t even clear whom I would ask at the Forest Service. Historian? Archivist? I got some phone numbers and emails, but no one returned the messages.”

Some of that effort looked into moving the Forest Service from Agriculture to Interior. A 2009 Government Accountability Office report concluded “a move would provide few efficiencies in the short term and could diminish the role the Forest Service plays in state and private land management … [If] the objective of a move is to improve land management and increase the effectiveness and efficiency of the agencies’ diverse programs, other options might achieve better results.”

The 2009 GAO report also cataloged other past consolidation initiatives. One was the colocation of wildland firefighting experts from the Forest Service, BLM, Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs to create the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho. That took place in 1965.

Where’s the Fire?

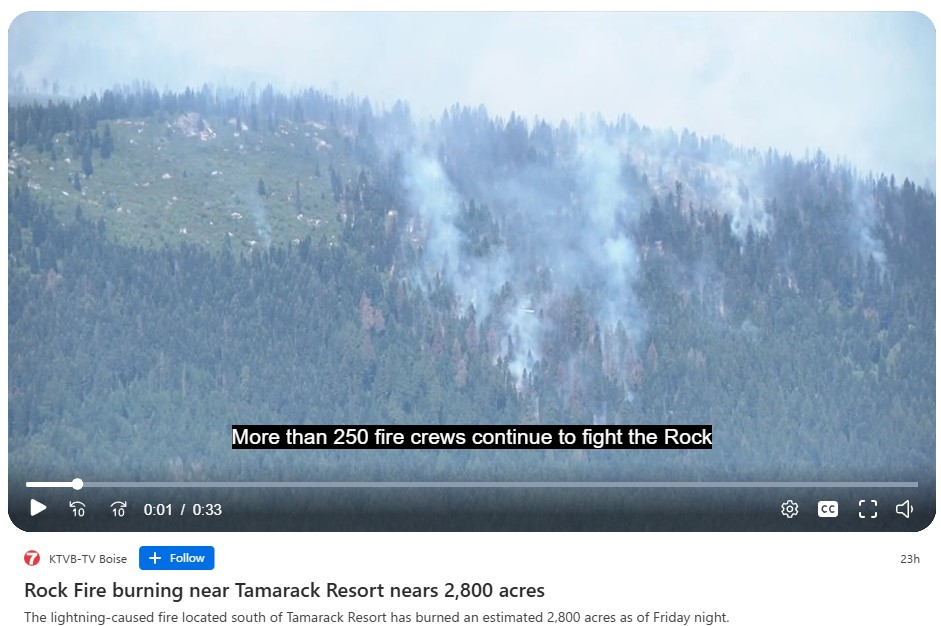

One particular problem drags public lands management off balance: wildfire.

While logging trees and grazing cows and digging trail occur far from the average American’s attention, forest fires are literally front-page news. The Forest Service routinely spends nearly half its annual budget fighting fire. It handles between 70 and 80 percent of the public land ignitions, with Interior agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management chasing most of the rest.

Federal firefighters have long chaffed at being just a tool in a larger agency’s land management toolbox, according to Freidman.

“There’s a tension between wildfire people and everybody else,” she said. “They got pay raises and nobody else did. They want to work for other wildfire people, because they feel they’re a national asset. They think they shouldn’t have others holding them back when they could be making money.”

But wildfire and public land management are woven together in a tight braid. Fire-dependent ecosystems cover most of the western United States. Local ranger districts not only map and monitor their surrounding forest for fire potential, their staffs often donate their time to the community volunteer fire department and ambulance service.

Removing fire duties from the Forest Service would “hollow out” the agency, according to Ellis.

“Fire is integrated in every program the Forest Service does,” he said. “Anything you do on public lands affects the fuel. It isn’t just burning slash piles. It’s how you graze range land. It’s timber harvest. That’s all fuels management. The fuel in Los Angeles fires [last January] was homes.”

During the hearing, Senator Klobuchar asked if there was a bigger plan to move the Forest Service, or parts of it, to some other cabinet agency. She particularly wanted to know about the fate of wildland firefighting.

Vaden replied that the president’s budget, not the reorganization plan, called for the centralization of wildfire services. In other responses, Vaden said the Missoula-based Fire Lab would not be moving, and that the Salt Lake City regional hub was chosen in part because it offered “aviation assets” that would help the Forest Service in the “administration’s plan regarding centralizing wildfire efforts.”

Congress had already shown resistance to other Trump administration moves. Last week, both the House and Senate Appropriations committees rejected a plan to wrap the Forest Service’s firefighting duties into a new wildland fire management service housed in the Interior Department. Despite a Trump executive order creating the consolidated wildfire service and Forest Service and Interior budget reports detailing how it would work, congressional budgeters put the 2026 wildfire allocations back in their traditional multiagency bankbooks.

“The committee is disappointed with the utter lack of regard for complying with Congressional intent on spending funds as appropriated,” the Senate Appropriations Committee bill report stated. On other pages, the Senate committee overruled Trump’s order changing the name of North America’s highest mountain from Denali to McKinley. And it blocked an Interior Department plan to hand over some unnamed small national park facilities to state management.

“Over my whole career, the president’s budget, if you took it as reality, was completely drastic,” Erickson said. “We always expected it was going to be moderated by the Congressional process. Up to this point with Trump, you hadn’t seen that. Maybe we’re seeing some good signs there.”