The U.S. Forest Service has not yet approved a plan to allow electric bicycles (e-bikes) on trails in the Lake Tahoe Basin, contrary to earlier reports. The Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit (LTBMU) is still in the process of evaluating a proposal that could potentially open up more than 100 miles of trails to e-bikes.

The Basin Wide Trails Analysis Project, which includes the e-bike proposal, is currently undergoing environmental assessment. The Forest Service expects to release the Final Environmental Assessment and a Draft Decision Notice in late August 2024. This will be followed by a 45-day administrative review period for those who have previously commented on the project and have standing to object.

If approved, the plan would allow Class I e-bikes, which are pedal-assisted and can reach speeds up to 20 mph, on designated trails. The proposal also includes the potential construction of new routes and upgrades to existing infrastructure.

The LTBMU received 660 comment letters during the public comment period in September 2023 and has been working to update the Environmental Assessment based on this feedback. The agency is also completing a required formal consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Currently, e-bike use is only permitted on National Forest roads and trails in the Tahoe Basin that are designated for motor vehicle use, in accordance with the Forest Service’s Travel Management Rule.

A final decision on the project is estimated to be released in November 2024. This timeline reflects the complex nature of the proposal and the Forest Service’s commitment to thorough environmental assessment and public engagement in the decision-making process.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/ltbmu/news-events/?cid=FSEPRD1192762

Supplementary Saw Accident and Near Miss Sharing:

National USFS Saw Accident / Near Miss Reporting Form (office.com)

Other opportunities to share:

- Wildfire Lessons Learned Center, Rapid Lesson Sharing (RLS) portal: https://lessons.wildfire.gov/submit-a-lesson.

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group, Fuel Geysering Incident Reporting Form: https://www.nwcg.gov/committees/equipment-technology-committee/national-fuel-geyser-awareness.

If you have any more information that you would like to share regarding your incident, please email your Regional Saw Program Manager.

- R1 – Adam Washebek, adam.j.washebek@usda.gov

- R2 – Brian Teets, brian.teets@usda.gov

- R3 – Kerry Wood (PoC), kerry.wood@usda.gov

- R4 – Brian Burbridge, brian.burbridge@usda.gov

- R5 – Mitch Hokanson, mitchell.hokanson@usda.gov

- R6- Aaron Pedersen, aaron.pedersen@usda.gov

- R8- Patrick Scott, patrick.scott2@usda.gov

- R9 – Shawn Maijala (detailed), shawn.maijala@usda.gov

- R10 – Austin O’Brien, austin.obrien1@usda.gov

National SPM – Dan McLaughlin (detailed), daniel.mclaughlin@usda.gov

By Melanie Vining, ITA Executive Director

By Melanie Vining, ITA Executive Director

I wouldn’t put myself in the “wing it” category, but if there is spectrum I’d not be at the “well-prepared” end either. Maybe somewhere in the middle. I’ve taken off on ten-mile day hikes with running shoes and a peanut butter sandwich, but I’ve also done weeklong backpacking trips and checked all the boxes: proper food, first aid kit, clothing for bad weather, etc. I’m…semi-prepared. But a recent event has underscored, for me, the importance of planning for the worst.

If you read my last blog post, you know I was injured in a horseback riding accident in May. In this case, I was prepared: I went for a short ride from my house, alone, but made sure I had my phone in my pocket and not in my saddle bag so in the off chance I should end up on the ground (where are these odds when I play the lotto?!), I’d have communication. In this case, a phone= preparedness. I was riding a good horse, one that had done hundreds of miles on trails and leading pack strings with me the summer before. I was leading a mule that had gone on most of those trips. Our skill set matched our journey. But, as they say, stuff happens.

So back to preparedness. People approach this topic differently, but I’ve had a lot of time to think about it in the last month (a LOT), and I feel like there is a “recipe” for being prepared for an outdoor adventure.

adventure.

- The first ingredient is sort of internal: fitness level and skill set. If you are embarking on a hike or other adventure more challenging or complex than you’ve attempted before, preparedness might look like training hikes and practicing certain skills ahead of time. Never tested the water filter? Maybe try that sucker out before it clogs, you don’t know how to troubleshoot, and you find yourself staring at a stagnant pond, choosing between imminent gastrointestinal malady or being really freaking thirsty.

- The second ingredient is gear: are you out for a few hours? A day? Weeks? What could you possibly encounter in that time? Weather, physical obstacles, wildlife…a list helps. Maybe bear spray isn’t important hiking in the Boise Foothills for the afternoon, but for the same 3-mile hike in the Selkirk Mountains, it’s essential. The three-season tent is dead weight on a July Priest River hike but it’s a life saver on an October trek in the high Sawtooths.

- Next in the recipe: communication. Does someone know where you’re going and plan to return? Do you have a way to call for help should you need it? Back to my horse wreck. I was ¼ mile from my house and less than that from our neighbors, but in a field that was totally out of sight from both. I hadn’t told anyone where I was going, since it was “just out the back door” and my husband and kids were at work and school. Had I not had my phone, I would have been stuck, surrounded by my unconcerned and equally invisible animals, for several hours before anyone missed me. But I’d planned ahead enough so I was able to call for help right away. Bring the phone where it works, invest in the satellite communication device. You can still “unplug” and not text for fun, but it could literally save your life. Tell someone where you’re going, too. Give them a map if they aren’t familiar with the area you’ll be in. Technology can fail, and a human back up plan is essential.

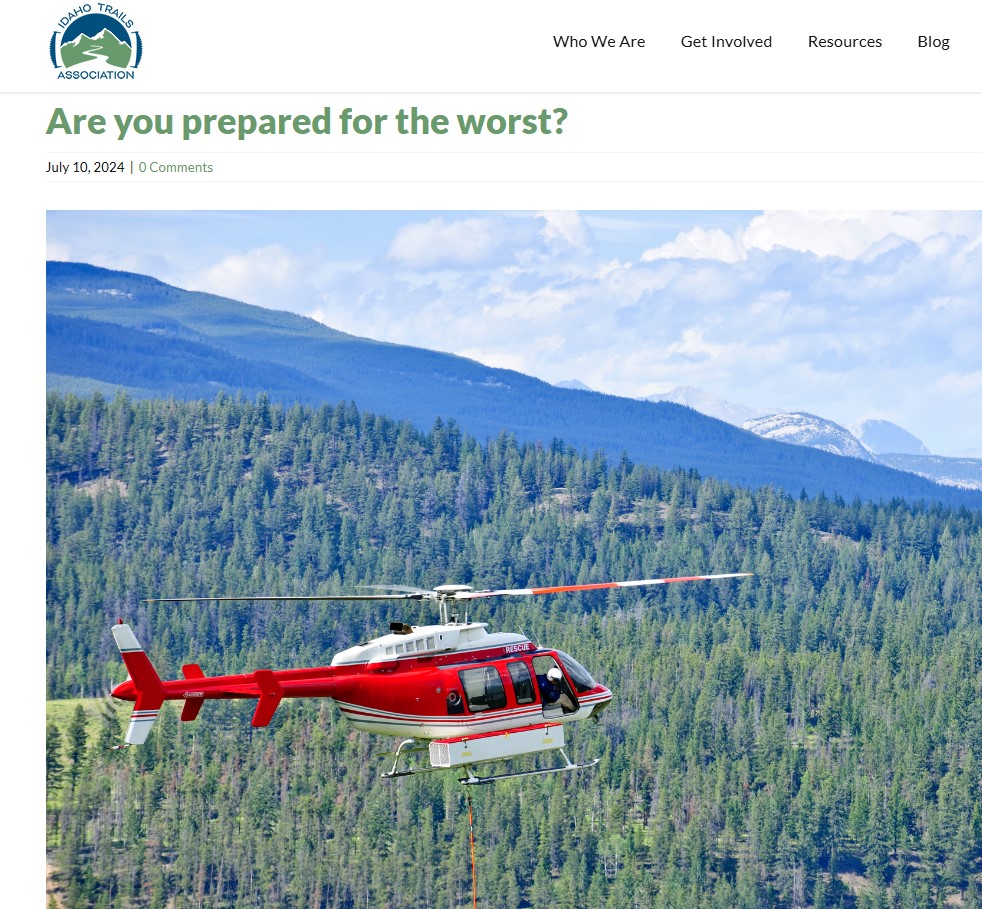

- Maybe most important is medical. Ideally, everyone should have basic first aid training and a basic first aid kit in their pack, vehicle, saddlebags, always. There are many resources for training and information; take advantage of them (or become an ITA crew leader and get Wilderness First Aid Training for free!). Sadly, there are injuries the best of the backpack first aid kits and even surgeon-level education and training can’t fix on the trail. Enter Life Flight membership. Last I checked (five minutes ago), the membership was 85.00/year. Average Life Flight bill: I’ve not done that math but our son’s bill- had we not had Life Flight coverage- when he was injured 6 years ago and flew from the Arco area to Twin Falls was over 25,000 dollars. I’m still awaiting my bill, unexcitedly, because even if you’re covered, seeing five figures on a paper that says BILL at the top makes the heart pound. And this is all before the patient enters the hospital for treatment. Certainly worth the membership, especially for us outdoor adventurers. You don’t need it til you…need it. Our family has flown this way more than we’d like, and we aren’t exactly kamikazes in the woods. Note: some insurance plans cover Life Flight- my husband’s does-so check yours as it may, and you can skip the membership.

- Last, and maybe this goes without saying for the active choir I’m preaching to but stay fit! I can’t count how many times everyone from my surgeon to nurses to physical therapists remarked that my good bone density (solid anchor for the screws and plates they had to “install”), and fitness would speed my recovery. My upper body strength has allowed me to get around on a walker vs a wheelchair, push myself up from chairs using only my good leg, and just be more self-sufficient in general (my husband still must put my socks on, sigh). The best way to be prepared for an injury we hope not to happen is to be as healthy and fit as possible.

- So, there it is. Risk management from my armchair here in rural Idaho. Plan, learn, practice, communicate. Get the 7.00/month Life Flight membership. But keep hiking and adventuring!

Do You Have a Lemonade Mindset? (What happed to Mel)

Just wanted to let you know where we are after three weeks of work done, and the rough plan I have for the remaining three. I have a bunch of pictures attached here and can send more if needed.

We have had a crew work on each of Renwyck, Antelope, and Gabe’s Peak. Progress has varied on each trail. Renwyck and Gabe’s Peak were fairly easy going for the first two miles before getting brushy and hard to find. Antelope got brushy and off-track very quickly. I actually ended up going out last week to visit the crews and find/flag the Antelope trail a little further out.

On the specs sheet, it lists Renwyck and Antelope as higher priority, so I was going to have the remaining three weeks focused on those two trails. I think I will likely need to visit the site again to flag both these trails further – unless you or someone on the trail crew can go do the same.

For Renwyck, the crews will basically be building new tread from where they left off. The old tread is there but very intermittent and not easy to follow. The nice thing here is that the trail does follow closely to the FS Quad Topo map and Avenza will be helpful in finding where to build going forward. I was planning on having two of the remaining weeks here.

For Antelope, the line on the Topo map is very wrong and this actually ended up hurting the crew as they went a good ways off tread trying to match that line. I got them back on the right track but would be surprised if they make it much past two miles, if that, with the one remaining week of work.

For the photos, the first four (0486, 0483, 0491, 0492) are work done on Antelope. The next two (0506 and 0507) are work done on Renwyck. The last (0494) is a good approximation of what both trails look like going forward – this particular picture is Antelope.

Let me know if this makes sense as the plan going forward. We’ll have a crew out that way next week (thinking Antelope for this) and I would love to hear back if you have any differing ideas.

Thanks,

Oliver Scofield

(he/him/his)

Program Coordinator

Idaho Conservation Corps

Idaho has an abundance of hiking trails to explore during the summer months, but being prepared when exposed to wildlife and areas with no cell service will help you have a good time. Hiking in the Boise Foothills and beyond can be exciting but requires preparation before venturing into the wilderness. There are 12 snake species in Idaho, including the Western rattlesnake and prairie rattlesnake, Idaho’s two venomous snakes.

It’s possible you could end up in the Idaho wilderness without cell phone service and surrounded by potentially dangerous snakes. So what will you do if you get bitten? Below, you’ll find tips on how to avoid the snake in the first place, how to prepare for your hike — and then what to do if the worst happens:

AVOIDING A SNAKE BITE In the U.S., roughly 8,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes yearly. To prevent a snake bite from happening when you’re out on a hike, below are some tips to consider from the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Prepare for your hike Wear over-the-ankle boots, thick socks, and loose-fitting long pants Don’t go barefoot or use sandals While on your trip Stick to well-used trails when exploring Avoid walking through tall grass and weeds Watch where you step Avoid wandering in the dark When going over fallen trees or large rocks, inspect the surrounding areas to make sure there are no snakes Be cautious when climbing rocks or gathering firewood Shake out sleeping bags before using them and inspect logs before sitting down

PREPARING FOR YOUR IDAHO HIKE Hiking on a new trail can be exciting, making it easy to get lost or hurt in a no-cell service area. It is essential to stay vigilant on designated trails. Below are some tips from the National Park Service to prevent getting lost: Review your route before you get on the trail Pack a compass or handheld GPS Be aware of trail junctions Watch out for information signs Keep an eye out for landmarks throughout the trail Call 911 if you have an emergency, like a rattlesnake bite. Remember, you don’t need a cell phone provider to use emergency services.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU DON’T HAVE A CELL SIGNAL Worst case scenario, you find yourself in a remote area with no cell service and potentially even hurt. Below are some tips for finding help if you’re in this situation:

Calling for help Many satellite emergency communicators can send text messages and have an SOS feature to send coordinates. Some iPhone users can make an SOS call through the lock screen. The call will automatically call a local emergency number and share your location information, according to Apple. One thing to consider is that iPhone 14 phone models and those after can use the emergency SOS feature with only satellite and not cellular data or WiFi coverage.

Self-rescue Calling for help when you’re deep in the Idaho mountains is determined on a case-by-case basis. Below are some general tips on finding help if you’re lost: Try getting back to a cell service area to call for help. If you feel lost, use a handheld GPS, compass or map to help get you back, according to the National Park Service.

If you’re lost and have no way to get help, following a drainage or stream downhill can be used as a last resort, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

When waiting for help, follow these tips, according to the Department of Agriculture: Immediately call dispatch or 911 and stay calm. A higher heart rate will pump the venom through your bloodstream faster.

Wash the bite gently with soap and water, and remove any tight clothing or jewelry around areas that may swell. If possible, keep the bite below heart level. This will prevent the venom from reaching your heart as quickly.

Do not restrict blood flow by applying a tourniquet or icing the wound. Many amputations from rattlesnake bites occur because the wound is iced or blood flow is restricted.

Do not try to suck the poison out with your mouth. The poison could possibly enter another cut in your mouth or be swallowed.